Global markets — equity and fixed income — have recently been buffeted by crosscurrents, including rising inflation, tighter financial conditions, the continued spread of the coronavirus (particularly in Asia), and evolving geopolitical tensions in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Global growth faces multiple headwinds, and central banks face the challenging task of reining in rising prices without tipping economies into recession. Richly valued, interest rate–sensitive growth equities have been hit particularly hard by higher interest rates, and volatility in credit markets has picked up too. Sequence of returns risk, or sequence risk, is the risk associated with the poor timing of negative investment returns materially impacting an investor’s ability to realize their investment objectives. The year-to-date performance of global markets highlights the importance of understanding the impact of sequence risk and how to manage it.

This risk is commonly discussed within the context of retirement savings and target date funds, as large drawdowns close to or early in retirement can have a significant negative impact on retirement outcomes. Why is sequencing risk most pronounced in the later stages of the retirement journey? Because as a member nears retirement, balances are typically at their largest level after years of saving and positive investment returns. At this point, large negative returns can result in large losses, and there is little time to recover. Once a member enters retirement, the issue is complicated further by the end of contributions, which makes it harder to replenish savings, and the start of distributions, which may mean there are fewer assets that can benefit from a potential market rebound.

Sequence of returns and glide paths

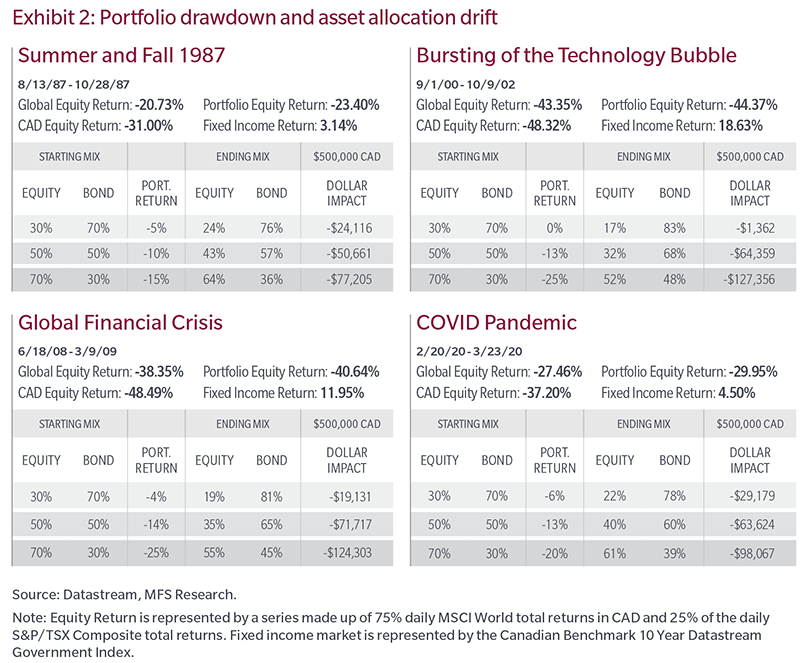

While there is general agreement that sequence risk is greatest close to or early in retirement, the degree and nature of the risk is not the same for all target date fund lineups. Glide paths can vary quite a bit across target date providers. Many plan sponsors express concern regarding the aggressiveness of the asset mix close to retirement. History shows that this concern is warranted as different asset mixes can lead to meaningfully different drawdown experiences for members. All else being equal, a portfolio with 50% to 60% equity at retirement (i.e., a typical “through” glide path) is likely to experience more damage than a portfolio with 20% to 40% equity at retirement (i.e., a typical “to” glidepath) in a significant equity market downturn.

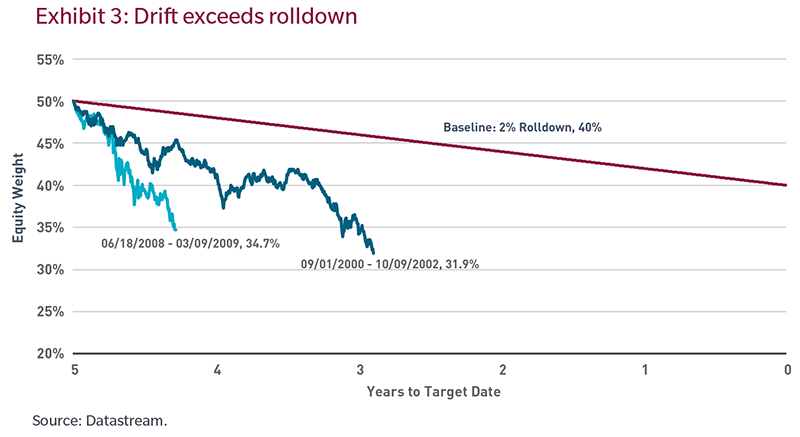

A secondary, more subtle concern is sometimes expressed around the slope of the glidepath. The idea being that steeper glidepaths de-risk at a faster rate resulting in lower exposure to equities when equity markets subsequently rebound. History in this case suggests that this concern is perhaps misunderstood or misplaced as equity drawdowns are often quick and violent and not a lot of glidepath rolldown occurs during the actual market downturn. What can be more impactful is the shift in asset allocation due to the large divergence in performance across asset classes. During an equity market downturn, equity weight can drift meaningfully below the intended allocation. Rather than focusing on the steepness of the glidepath, plan sponsors and members may be better served by focusing on their target date provider’s rebalancing philosophy and practices. Disciplined rebalancing can help ensure that equity levels are closer to their intended target when markets do rebound.

Equity market selloffs

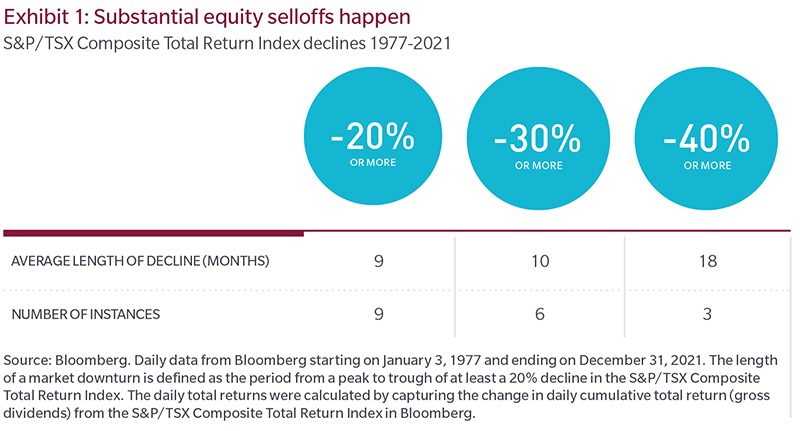

Over the past 40+ years, the S&P/TSX Composite Total Return Index has experienced nine major selloffs (defined as a selloff of 20% or more), with six of those selloffs exceeding 30% and three exceeding 40%. The average length of a major equity selloff can vary quite a bit, ranging from short, violent selloffs, such as the October 1987 and March 2020 declines, which lasted less than three months, to more prolonged selloffs, like the bursting of the tech bubble in 2000, which took well over a year to fully play out.