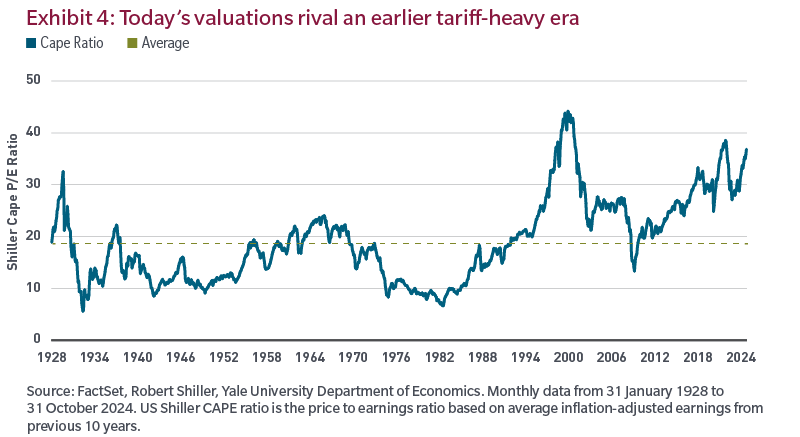

While prices today aren’t as high as they were during the 1990s internet bubble, given the historical return of risk assets, we shouldn’t be too surprised to see that they compare to the levels of the late 1920s. However, I’m not suggesting a redux of October 1929, or another Great Depression, as there are too many differences between the periods.

While valuation is one similarity, valuation alone can be a dangerous investment signal. Importantly, investors need to consider the pathway of future earnings, the denominator in the chart above, and the prime determinant of the prices investors will pay. Which brings me to one other similarity to the late 1920s: tariffs.

In 1929, investors began to discount the Republican Congress’s plans to tariff over 25,000 goods entering the US. This mattered to investors because, while tariffs make US goods more attractive to domestic buyers, they drive up costs for US producers sourcing goods outside the country as well as consumers. While there were other catalysts heading into October 1929, the prospects of the Smoot-Hawley tariffs were a factor that changed both how investors thought about future profits and what they were willing to pay.

To be fair, long before the 2024 election, input costs had risen as capital and labor costs jumped. But companies were largely able to offset those pressures by passing on higher prices to customers and cutting spending in non-mission critical areas. What has changed is consumers have begun substituting goods and services where necessary, driving prices and inflation down, and lowering corporate spending in unnecessary areas. With the low-hanging fruit already plucked, profit margin�protecting maneuvers will be harder to achieve in the future, bringing forward a new paradigm with far greater return dispersion in benchmarks.

In conclusion, less government involvement in the economy and markets is long overdue and welcome. But I think investors need to consider what a reduced government role may mean for the profitability of projects and businesses that are unable to offset rising cost pressures. As a result, I think Trump 2.0, specifically smaller government, may upend the performance dominance of passive investing.

Endnotes

1 Source: Bloomberg, S&P 500. Cumulative and annualized return calculated using monthly data from 31 January 2009 to 31 October 2024. Returns are gross and in USD.

Source: Bloomberg Index Services Limited. BLOOMBERG® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affi liates (collectively “Bloomberg”). Bloomberg or Bloomberg’s licensors own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Indices. Bloomberg neither approves or endorses this material or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, or makes any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.

“Standard & Poor’s® ” and S&P “S&P® ” are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC (“S&P”) and Dow Jones is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC (“Dow Jones”) and have been licensed for use by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and sublicensed for certain purposes by MFS. The S&P 500® is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, and has been licensed for use by MFS. MFS’ Products are not sponsored, endorsed, sold or promoted by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones, S&P, or their respective affi liates, and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones, S&P, their respective affi liates make any representation regarding the advisability of investing in such products.

The S&P 500 Index measures the broad US stock market. It is not possible to invest directly in an index.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are subject to change at any time. These views are for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as a recommendation to purchase any security or as a solicitation or investment advice. No forecasts can be guaranteed. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.