June 2024

Boomer, Consumer!

Those who have, spend. Those who don’t, borrow… then spend.

Soumya Mantha, CFA

Research Lead Analyst

Investment Solutions Group

Michael Miranda, CFA

Strategist

Investment Solutions Group

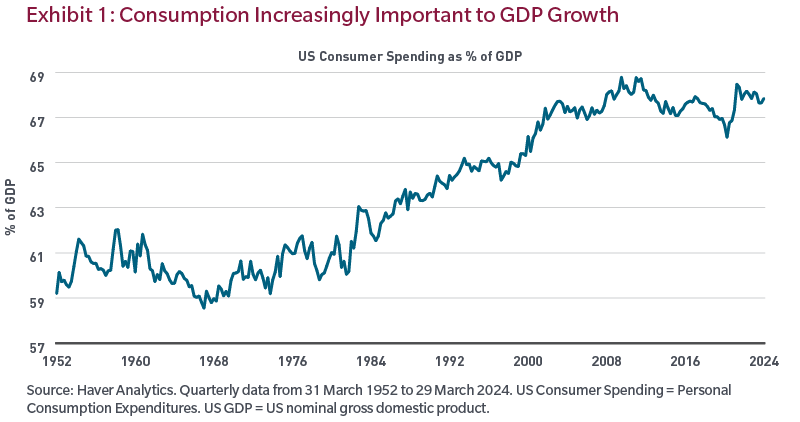

Consumers are the backbone of the US economy and have been the primary source of economic growth for nearly a century. In fact, consumption has been a growing contributor to economic activity, even during times of recession.1 Despite inflationary pressures, consumption has proven to be a boon to the economy following the pandemic. Several factors have contributed to this surge in demand, including long-term demographic changes, differences in spending by income distribution and broadly rising wealth levels. The question is, can these forces continue to fuel consumption growth going forward?

The US economy has not always been driven by consumption. Spending patterns shifted in the 1920s as factory productivity increased, the stock market boomed and wealth levels rose. The emergence of financing companies during this time opened doors to new ways for families to borrow money. World War II marked another pivotal shift when wartime production pulled the United States out of depression. Young adults saw spending power rise rapidly in the late 1940s amid an ample supply of jobs and rising wages. New federal programs led to a rise in suburban living, which increased spending on housing and products that modernized living. Furthermore, the higher levels of spending during this time were supported by a growing population as birth rates hit record levels. With continued technological advancements and new products entering the market each day, household consumption continued to rise during the post-war era. Today, consumer spending accounts for nearly 70% of US GDP.

The continued growth in personal consumption expenditures has been the driving force for America’s dominance in global economic growth over the past 40-plus years. A strong consumer powered the US economy in 2023, despite slowing global economic activity, as other developed market economies, which on average exhibit lower consumption levels, found themselves falling behind. These economies relied more on other factors to fuel growth. For instance, a sizable contribution to economic growth for Canada and parts of Europe comes from trade and natural resources, which depend on demand from global trading partners. A slowdown in global trade and demand for natural resources impacted these countries, whereas the US benefited from strong domestic demand. In Japan, consumers have a higher propensity to save rather than consume. Instead, the country relies on manufacturing and services such as financials to fuel economic activity. Furthermore, these economies tend to have a greater dependence on government spending compared with the US. There are other structural differences such as the variable rate mortgage structure across many non-US developed markets, which increase household debt payments as rates rise, reducing consumers’ capacity to spend.

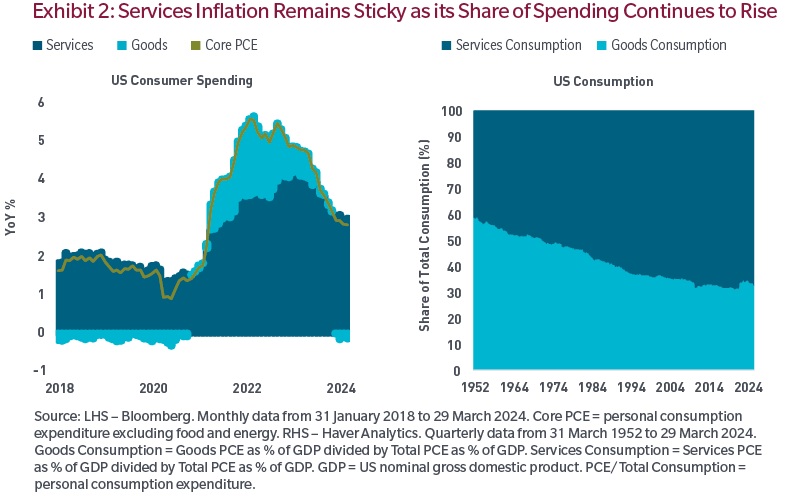

In 2021 and 2022, the US saw a significant spike in inflation amid pandemic-related supply chain disruptions, massive fiscal stimulus and geopolitical tensions. Consumer spending surged, partially due to higher prices, but also as a function of consumers looking to get out of their houses after being bottled up for nearly two years. Households increasingly spent on services such as vacations, eating out, self-care and wellness rather than on goods — a trend that emerged pre-pandemic but has been exacerbated in recent years. While high inflation subsided, primarily due to prices for goods entering deflationary territory, it has not decreased as much as hoped as services inflation remains elevated. The US Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes from 0.0% to 0.25% to a targeted range of 5.25% to 5.5%, a move to increase borrowing costs to reduce demand, has had little impact on consumer spending to date.2

The spark in consumer spending post-Covid was driven by excess savings households accumulated during the pandemic via increased government transfer payments and reduced spending on discretionary items during the lockdown. These accumulated savings have dissipated as prices rose and consumers continued to spend. Despite lower savings and higher interest rates, consumer spending habits continue to be fueled by a strong jobs market, high absolute levels of wealth and increasing use of debt.

With consumer spending making up more than two-thirds of the economy, higher economic growth relative to history is likely to be dependent on a strong consumer. We observe several shifting dynamics in consumer spending that may impact the US economy’s trajectory.

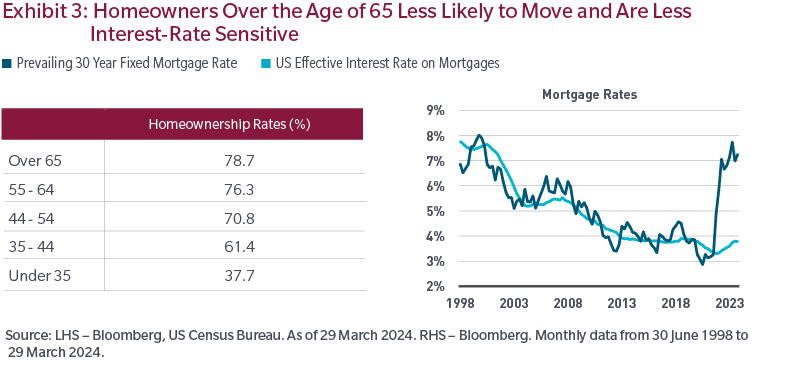

Aging Population

Demographic shifts have played a major role in changing consumer dynamics in the United States for more than half a century. Over the past 60 years, improved living standards and advances in health care helped double the share of the population over age 65. That age bracket’s share of consumer spending also rose considerably over the past two decades. Homeownership and wealth levels among those over 65 provided them with the capacity to spend more than any previous generation. Their homeownership rates are far higher than for other age groups, and many either own their homes outright or have mortgages that are locked in at very low fixed rates. With the current limited supply of existing homes on the market and increasing demand for housing, prices for homes have skyrocketed in recent years, providing older generations with significant levels of home equity.

Additionally, historically high levels of retirement assets and higher interest rates earned on their savings have allowed Baby Boomers to enjoy greater spending capacity than any previous generation. Specifically, defined contribution and individual retirement account assets reached over $11 trillion at year-end 2023,3 while money market funds, some of which are held within retirement accounts, recently reached over $6 trillion as investors took advantage of higher yields.4 They are now benefiting from significant levels of interest income not seen from relatively safe assets since before the global financial crisis.

In retirement, consumers tend to alter their spending habits. In early retirement, they tend to search for ways to lower expenditures on goods (e.g., lower prices, bargain deals, etc.) while shifting spending towards services such as travel. As retirees age, spending for health care increases. Health care spending has seen the largest uptick in its relative contribution to personal consumption expenditures over the last sixty-plus years, rising from 4.7% of PCE in 1960 to 16.3% at the end of 2023.5

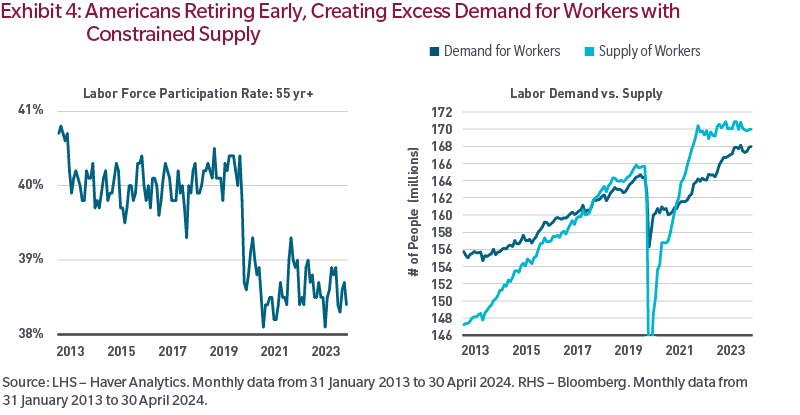

Labor Market

A robust labor market has been a key driver for consumer spending. Employment growth has been strong and the unemployment rate is at near historic lows. One of the main reasons for the low unemployment rate is declining labor force participation. Since 2000, the participation rate has declined broadly, primarily driven by an aging population and a rising number of retirees.

Following peak-Covid, participation rates started to recover to pre-pandemic levels. However, participation from those 55 and over has not bounced back, as many Americans chose to retire early, kickstarting the “Great Retirement.” While a rise in retirement was expected as Baby Boomers aged, Covid-19 sped up the retirement wave and the number of workers exiting the workforce surged again. This created excess demand for workers, while supply became constrained. With very low unemployment rates and a high labor force participation rate among the 25 to 54 age group (approximately 84%), companies may find it challenging to fill job vacancies.6

Income Distribution and Spending

Breaking down the consumer picture by income distributions provides additional clarity regarding the continued strength in spending. Higher relative income quintiles are responsible for most aggregate and discretionary spending, with the top quintile of earners accounting for approximately 40% of aggregate spending in the US.7 Measures taken by the Fed to constrain demand has had limited impact on this group for a few reasons, including higher levels of homeownership and lower levels of revolving consumer credit required to fund their lifestyles.

Unemployment rates have been low, yet consumer sentiment has been muted. Despite record-low unemployment, wage growth has remained below the rate of inflation, eating into consumers’ purchasing power. Rising food costs have been particularly problematic for lower income consumers, with prices rising roughly 20.7% in the past three years, outpacing wage growth.8 Some consumers, particularly younger and low-income cohorts, are starting to feel the pressure of higher costs. They have increasingly used credit and “buy now, pay later” schemes to finance both essential goods and services. To illustrate, outstanding credit card debt spiked to $1 trillion at the end of 2023, a number which is not inclusive of buy now pay later schemes.9 Debt burdens were compounded as the rise in credit card balances coincided with rising interest rates with the average credit card interest rate exceeding 20% today.10 However, in aggregate, household debt service payments make up less than 10% of disposable income and while credit card delinquency rates have started to rise, they are well below levels that would historically be deemed worrying.11

We believe that consumer spending will continue to be the driving force behind US economic growth. In the past few years, spending has been supercharged as demographic shifts have played out, coupled with the aftereffects of the pandemic lockdowns. Although those extra-high levels of consumer spending growth are unlikely to continue, it is reasonable to expect consumer spending to remain high relative to history given the growing number of well-funded retirees, overall wealth levels and the decreased sensitivity to interest rates of many consumers, especially those with the highest propensity and capacity to spend. Despite this, some consumers are likely to continue to feel squeezed by higher prices, particularly the younger and lower income brackets. We are seeing a rise in delinquency rates on credit cards and auto loans while overall job growth is showing signs of a modest slowdown. However, none of these metrics are indicative of a broader problem with the consumer yet. Should monetary policy remain restrictive for longer and unemployment start to tick up, some US consumers may face challenges.

Endnotes

1 Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, “Strength in consumer spending does not necessarily imply low probability of recession”, 2 January 2024, Strength in consumer spending does not necessarily imply low probability of recession - Dallasfed.org.

2 Source: Bloomberg. As of 30 April 2024.

3 Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Defined Contribution Pension Funds: Total Financial Assets, Level [BOGZ1FL594090055Q], IRA and Keogh Accounts: Total [IRA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, on 14 May 2024. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOGZ1FL594090055Q, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IRA.

4 Source: Bloomberg, Federal Reserve. As of 29 December 2023.

5 Source: Haver Analytics. 1960 = 31 March 1960, 2023 = 29 December 2023. Health Care PCE as % of Total PCE. PCE = personal consumption expenditures.

6 Source: Haver Analytics, as of 30 April 2024.

7 Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of 31 December 2022 (latest available).

8 Source: Bloomberg. Monthly data from 31 March 2021 to 29 March 2024. Food prices = Food consumer price index. Growth in food prices is cumulative.

9 Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit”, as of February 2024. Data as of 29 December 2023.

10 Source: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Credit Card Interest Rate Margins at All-Time High,” 22 Feb 2024. Credit card interest rate margins at all-time high | Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (consumerfinance.gov).

11 Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Household Debt Service Payments as a Percent of Disposable Personal Income [TDSP], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TDSP, 3 May 2024.

The views expressed herein are those of the MFS Investment Solutions Group within the MFS distribution unit and may differ from those of MFS portfolio managers and research analysts. These views are subject to change at any time and should not be construed as the Advisor’s investment advice, as securities recommendations, or as an indication of trading intent on behalf of MFS.